Yellowstone Winter: A Bison's-Eye View

A race between starvation and spring

Sometime in fall, well before winter officially arrives, snow comes to Yellowstone’s Lamar Valley. Those first white dustings—while lovely to behold—mark the beginning of the annual race between starvation and spring for park bison.

As snow accumulates, calves born just months earlier experience their first winter at Mom’s side. They learn to use their head to move—to bulldoze—snow and uncover the dried grasses that will nourish them during the next four to five harsh months. With a multi-chambered stomach, bison are built to get maximum nutrition from minimum rations.

But eventually snow piles up. And colder temperatures may create a layer of ice within the snowpack that moves bulldozing from difficult to nearly impossible. In either case, bison use more energy pushing snow or ice out of the way than they gain from eating the dried grasses they uncover. Starvation starts to pull ahead in the race.

As even more snow falls, hungry bison respond to the urge to migrate from Yellowstone’s higher reaches to the Gardiner Basin in search of less snow and more dried grass. Lamar Valley bison begin a journey of forty or so miles.

Bison know they must conserve energy during winter so they select the most efficient way to reach the Gardiner Basin. That brings our national mammal front and center with the first human-caused danger they face during migration: walking on plowed roads and dodging cars, trucks, and buses. Impatient or careless drivers have injured or killed bison with their vehicles.

Most of the bison eventually reach our small town of Gardiner at Yellowstone’s north gate. Our school’s football field is a place many bison choose to graze and rest and conserve energy after their long journey.

But the journey isn’t over. As winter continues, so does the migration. The bison leave Gardiner, pass by or through the famous Roosevelt Arch (to the right in the photo above), and continue their trek toward the basin—and the grazing—now so close. These two bison are walking in the park on Old Yellowstone Trail, a gravel road that meanders the final four miles from Gardiner to the park's northern boundary.

As this photo taken in early February shows, the Gardiner Basin has less snow and better grazing for this mother and her calf. Survival starts to pull ahead in the race. But winter isn’t over and human-caused danger lurks nearby.

Each winter the National Park Service hazes some migrating bison into the Stephens Creek Capture Facility—”the trap”—that lies within the park on the bison migration route. This photo shows one of four mounted NPS staff that I watched close in on this group of bison and haze them toward the trap.

After capture, processing begins. I have watched processing during a tour offered by NPS to members like myself of conservation organizations and to members of the media.

I watched as a squeezing device held a grunting, frightened, big-eyed bison in place and an NPS biologist used a large needle to draw a blood sample. Once released, the bison charged into a corral to join other captives. Bison are processed one after another, but a few buck and kick so hard they are passed through untouched.

Afterwards, many of the captured bison are shipped to slaughterhouses outside the park. Native American tribes divide the meat and hides.

Some of the captured bison are quarantined and eventually shipped to Fort Peck Indian Reservation in northeastern Montana. From there they may in turn be sent to other tribal nations that want to bring revered bison back onto their land and into their lives. In December of 2021, for example, the Yakama Nation in Washington and the Modoc Nation in Oklahoma each received twenty-eight Yellowstone bison from Fort Peck.

Death-by-trap is one of the two types of human-caused mortality awaiting our national mammal each winter. Many bison—sometimes hundreds—that avoided the trap die at the rifles of a firing squad of shooters in Beattie Gulch, two miles farther along the migration route and just barely beyond Yellowstone’s northern border.

The bison in the photo above were part of a group of two dozen that I watched grazing and walking in a protected area just outside the park late one February. In the background are shooters waiting for the bison to go where they can be shot. I counted more than twenty vehicles crowding the roadside and at least thirty-five people watching and waiting. I was thankful to see these bison turn around and walk back into the protected area.

This controversial hunt outside the park and capture within the park are required by the outdated Interagency Bison Management Plan—the IBMP. That plan was written years ago by a court-ordered coalition of the National Park Service, US Forest Service, USDA’s Animal & Plant Health Inspection Service, Montana Department of Livestock, and Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks. Later, the InterTribal Buffalo Council, the Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes, and the Nez Perce Tribe joined the IBMP.

Goals of the IBMP include keeping bison confined within Yellowstone and reducing the park’s population from around 5,000 to 3,000 bison. Each year IBMP members decide the number of bison that will die in winter. This winter that number is 900, but the Nez Perce tribe wants fewer bison removed.

The IBMP rationalizes this carnage as a way to protect Montana livestock from brucellosis, an infection caused by bacteria. Livestock with brucellosis may abort calves, causing ranchers to lose money. Bison can transmit brucellosis to cattle, but there has never been a documented case of that transfer in the wild. Brucellosis transfer originally went in the other direction: cattle infected bison in the early days of the park when cattle were kept in Yellowstone to provide milk and meat for visitors.

Even if bison were allowed to roam freely outside the park and did transmit brucellosis to some livestock, the world would not end. Free-roaming elk have transmitted brucellosis to cattle many times, and Montana’s livestock industry has survived, regardless of dire predictions of the financial cost of infection. Though guilty of spreading brucellosis, elk are not confined to the park or trapped like bison. Elk are not treated as livestock and controlled by Montana’s Department of Livestock as bison are if they somehow escape the park. Elk are trophies to be hunted and displayed. Bison are brucellosis scapegoats to be shot and slaughtered.

These bison have avoided being trapped or shot and graze safely during late winter in the Gardiner Basin among glacial erratics, boulders deposited here more than 10,000 years ago as glaciers from the last Ice Age melted. Bison—such incredible survivors—have endured numerous Ice Ages and avoided the die offs in which other large animals such as mastodons, wooly mammoths, and camels vanished.

The animal we call bison started as a much smaller grazer in southern Asia that began migrating northward and growing larger two to three million years ago. Eventually bison’s evolving ancestors crossed the Bering Land Bridge and slowly followed their noses southward to the Great Plains. Some experts believe bison eventually fled to Yellowstone to escape the slaughter during the 1800s on the plains. Today the park contains our nation's last remaining continuously wild bison.

While it may appear from this photo that there is nothing in this landscape that could possibly feed a bison, that’s not the case. One day in late winter, after standing and watching this bison and a number of others graze, I dropped to my hands and knees and inspected the ground. To my delight I found tiny, new, green shoots hidden among last year’s dried stalks. Those tiny shoots are the final fuel these magnificent survivors need to win that annual race between starvation and spring.

Thanks for joining me in this Love the Wild!

If you enjoyed this photo essay, please spread the joy and share it with others.

If you haven’t yet subscribed, I hope you will. It’s free.

You’ll receive a Love the Wild letter in your inbox each week. In addition to photo essays such as this one, you’ll enjoy a variety of podcasts, slideshows, commentaries, excerpts from my books and more. With each, I hope to warm your heart and excite your mind as we share moments with wildlife and in wild lands.

I love reading your thoughts and reactions.

I write and photograph to protect wildlife and preserve wild lands.

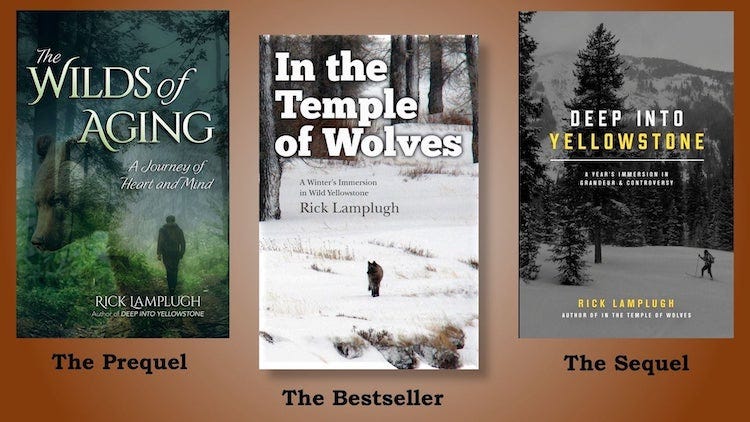

My bestselling In the Temple of Wolves; its sequel, Deep into Yellowstone; and its prequel, The Wilds of Aging are available signed. My books are also available on Amazon unsigned or as eBook or audiobook.

These animals are such survivors despite the efforts of some humans. It is hard to believe that the brucellosis myth has persisted for so many years. Thank you for sharing this again. Maybe someday science will be followed, and the bison will not be the scapegoats.